Among all the techniques of modern marketing, there is a whole class of them whose use is based on the objective results, obtained by rigorous scientific method, of the in-depth studies of psychology. Not only to promote a product, but also to outperform the competition.

Since one cannot openly denigrate what another brand produces (the law forbids it), one leverages unconscious mechanisms to favor one’s own at the expense of another, appropriately “guiding” the consumer.

Without often the latter even realizing it. Let’s look in detail at one such marketing tool called the “decoy effect” or, in English “decoy effect” (with decoy properly meaning “false target” or, indeed, “bait”).

Don’t believe it? Get to the end of the article and you will find many practical examples and a video of an experiment.

What is the Decoy Effect (decoy effect)

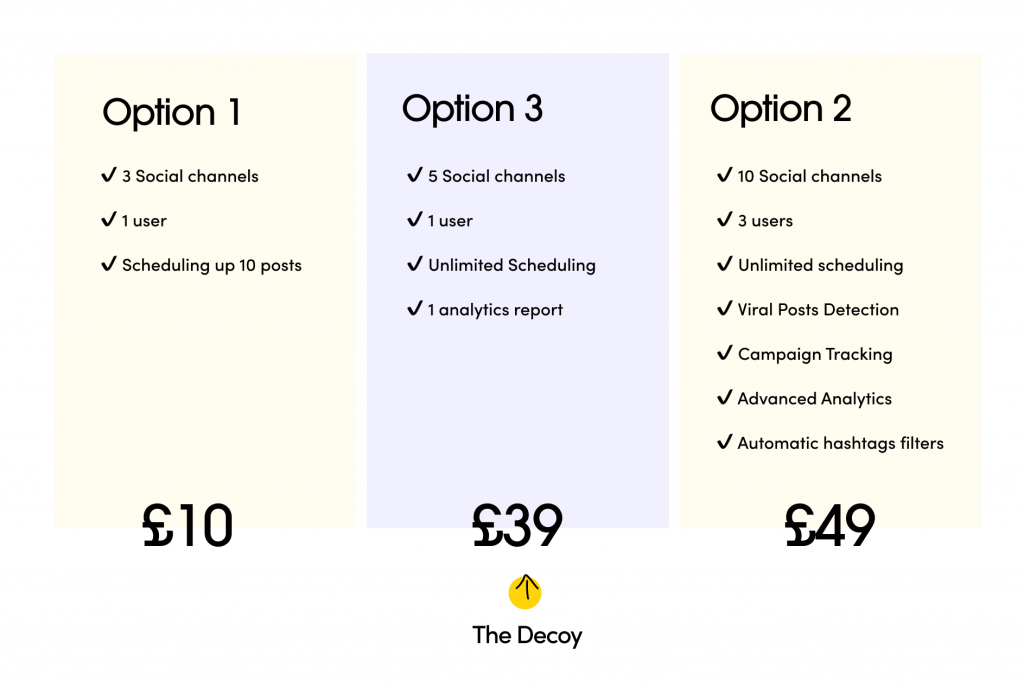

The most proper and strict definition of the decoy effect is “that which induces changes in individual preferences between two choice options, when a third, which was not present before, is introduced.”

This additional option, to have a “decoy effect,” must possess characteristics such that it is, as they say, “asymmetrically dominant.”

The concept of “asymmetric dominance,” a marketing jargon term that, however, much more properly and correctly should be called “anisoprodynamic” = “unequally promoting,” indicates a certain action.

That is, to emphasize, among three or more options, to the exclusion of the third, more one of the remaining two than the other, without “symmetry,” between them

How does it affect the psyche of individual consumers

The primary purpose of those who make use of the decoy effect, as part of marketing campaigns, is not to steer individual consumers toward their own products, but rather to keep them away from those of other competing manufacturers. Manufacturers operating in the same market segment, of course.

By turning consumers away and disinviting them from buying the products of competing firms, it will, indirectly, have the effect of turning their attention toward ours. So, even without promoting them directly, that will be the result in the end. Only, achieved vicariously.

Marketing bait effect, history and practical examples

The earliest recorded description of the decoy effect is dated 1981. Three scholars, namely: Joel Huber, John Payne and Christopher Puto, in an academic paper jointly presented at an economics conference, then republished in a journal the following year.

Conducted as a study with carefully selected participants, their experiment debunked previous theories of “heuristic similarity” and “conditional regularity.” These asserted that a new product would divert consumers from choosing the original one and, thus, cause the company marketing it, economic harm. Thus with no advantage over competing products.

Bait Effect Examples

To understand the mechanism well in detail, we will give some practical examples.

Let us imagine a situation where, initially, only two products are offered at two different prices. The products are of the same kind (e.g., a tablet) but in different setups and with more or less accessories provided to accompany the main product.

We mark these two business proposals with A and B.

- A – 900-watt vacuum cleaner sold for 89 euros (without accessories)

- B – 1200-watt vacuum cleaner + accessory bag + complete set of nozzles of various sizes and lengths, sold for 149 euros

In such a scenario, consumers’ choices would preferentially lean toward the proposal with the best price-quality ratio. However, it is not so immediate to realize

That proposal B is the one with the best ratio.

In fact, B offers 35 percent more power, plus several enclosed accessories, all for a price about 67 percent higher. Not little then. Sure, it offers a full set of sccessories, but what is the real value of those accessories, would they justify the higher expense compared to proposal A?

Let us now introduce a third proposal C

- C – 1000-watt vacuum cleaner, complete with two additional suction nozzles, sold at 129 euros.

At this point the consumer thinks that, for only 20 euros more, he can take home a vacuum cleaner that is more powerful (1200 watts versus 1000) and with several other accessories included in the price, plus the bag for storage.

So now the best proposition has become, in the eyes of the consumer, definitely the B. And here we have just seen the decoy effect at work, factually.

The same technique is used continuously in, for example, movie theaters to sell popcorn or even in Starbucks, Mcdonald’s etc etc.

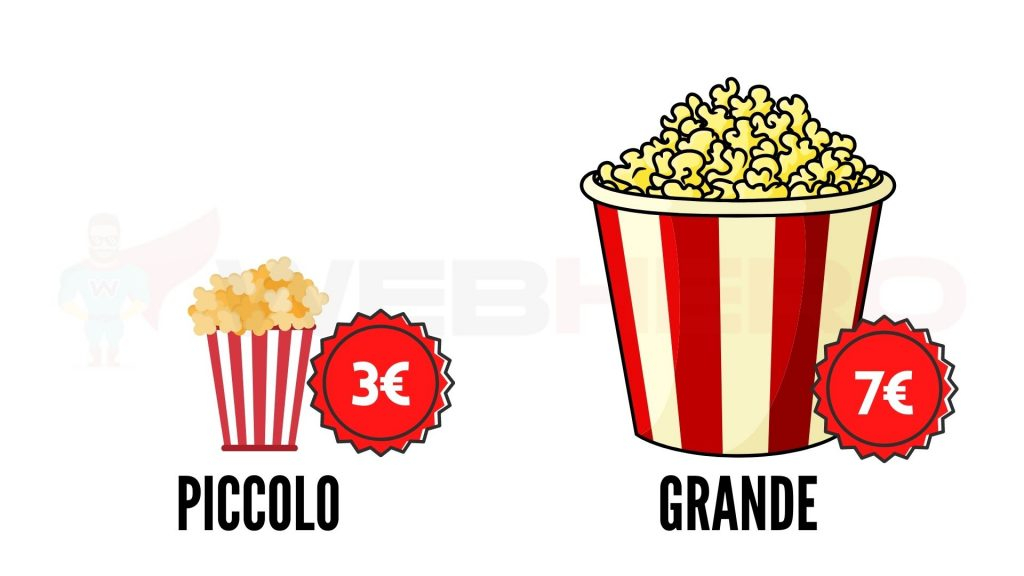

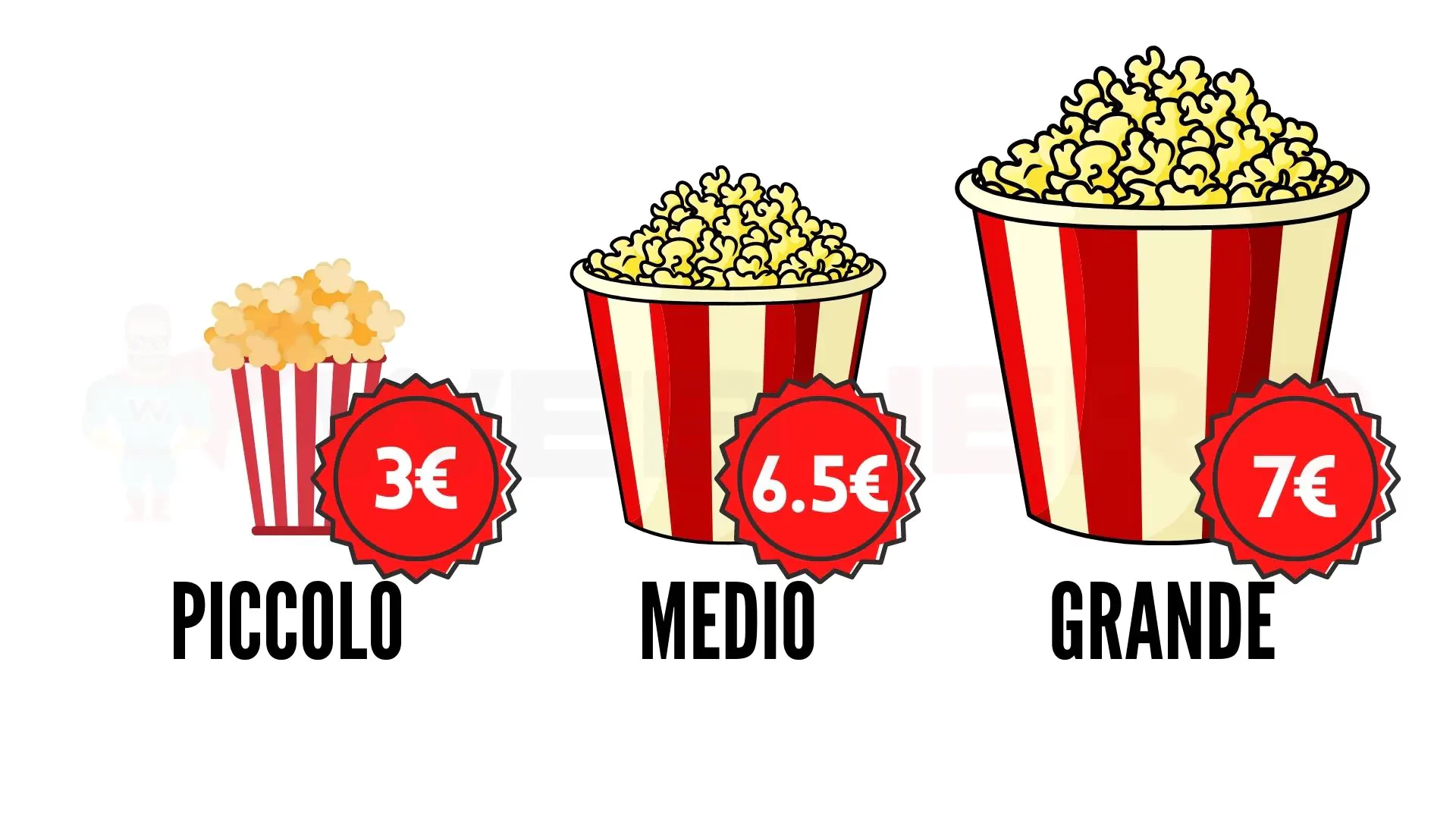

See this example: there are two sizes of popcorn sold in cinemas.

At this point almost all consumers will go for the 3-euro format because they will see the 7-euro format as very distant in price.

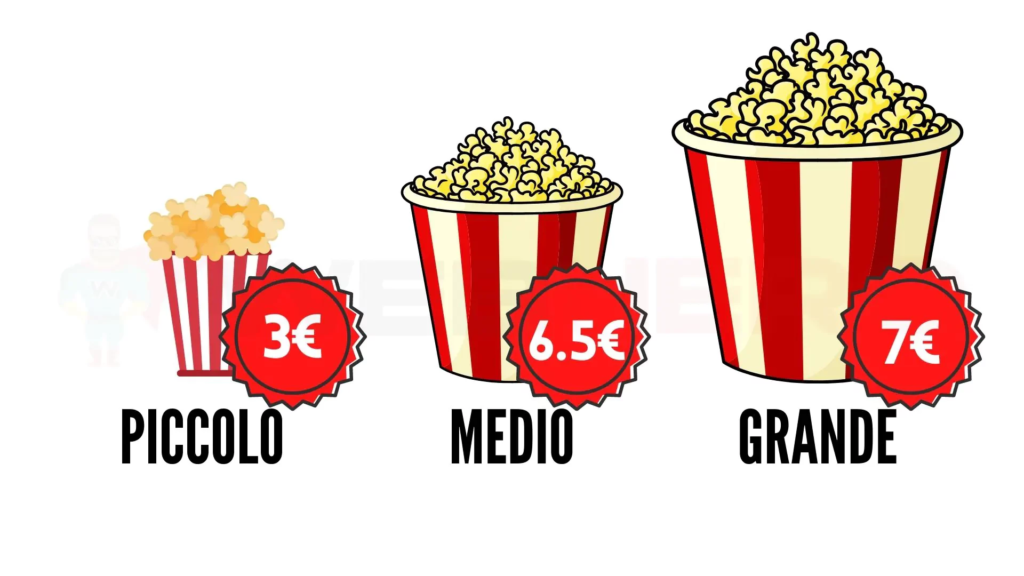

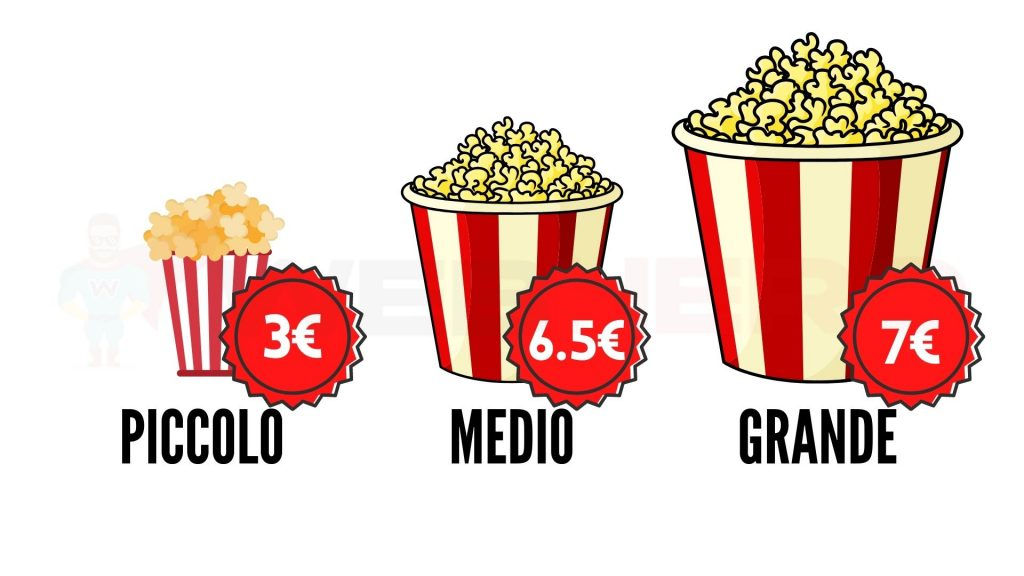

At this point the Bait effect comes into play. The vendor proposes 3 options, and the middle one is very close to the one that costs the most.

Let’s look at the example now.

As if by magic, the vast majority of users finding the larger package and comparing it with the average one will be inclined to buy that one for only 50 cents more. The shopkeeper will succeed in his intent to raise the take from 3 to 7 euros. Can you believe it?

+ There are no comments

Add yours